Beautiful Pencil Sketches Biography

source(google.com.pk)Few artists can rival the standards of excellence achieved by Master Artist Terry Redlin over the past 30 years. He is truly one of the country's most widely collected painters of wildlife and Americana. For eight consecutive years, 1991 through 1998, Redlin has been named America's Most Popular Artist in annual gallery surveys conducted by U.S.ART magazine. His induction into U.S.ART's Hall of Fame in 1992 followed the magazine's poll of 900 galleries nationwide which, that year, placed five of Redlin's limited editions in the top 11 in popularity. Over the life of the poll, 30 prints have been included in that list. His use of earthy colors, blazing sunrises and sunsets and nostalgic themes are often cited as the reasons for his immense popularity.

Redlin's interest in out-of-doors themes can be traced to his childhood in Watertown, South Dakota. A motorcycle accident ended his dream of becoming a forest ranger, and he opted to pursue a career in the graphic arts. He earned a degree from the St. Paul School of Associated Arts and spent 25 years working in commercial art as a layout artist, graphic designer, illustrator and art director. In his leisure time, he researched wildlife subjects and settings.

In 1977, at the age of 40, Redlin burst onto the wildlife scene when his painting "Winter Snows" appeared on the cover of The Farmer magazine. By 1979, demand for his work had become so great that he left his art directing career to concentrate on painting wildlife.

Since then, Redlin's meteoric rise has been unparalleled in the field of contemporary wildlife art. In 1981 and 1985, he won the Minnesota Duck Stamp competition, and in 1982, the Minnesota Trout Stamp contest. He also placed second that year in the Federal Duck Stamp Competition. He has been honored as Artist of the Year for Ducks Unlimited (National and Minnesota), and as Conservationist of the Year-Magnum Donor by the Minnesota Waterfowl Association for his gifts of entire print collections. The National Association of Limited Edition dealers has three times presented him with the "Lithograph of the Year" award for excellence in the medium.

In 1985, Redlin added an entirely new artistic direction, limited edition collector plates. To date, he has released more than 30 editions, many of which are now available only on the secondary market. In addition to fine art and collector plates, Redlin's images also appear in a variety of collectibles and decorative accessories. Cabins, homes and church sculptures adopted from some of his most popular art prints join music and keepsake boxes, steins and ornaments in collectors' displays.

In 1987, Redlin began exploring his interest in Americana subjects and nostalgic scenes of yesteryear, painting several images for his American Memories and Country Doctor Collections. Since then, his annual Christmas prints have attracted thousands of collectors from coast to coast.

In 1992, he completed his most ambitious work to date, painting each line in the first stanza of "America the Beautiful". All eight, which depict American life from the settling of the west to the present day, were released as limited edition prints over a three-year period, ending in January, 1995. The series has been showcased in art and consumer magazines nationwide, and it has been acclaimed by thousands of collectors. "Terry Redlin Paints America the Beautiful", a video presentation produced by Hadley House, earned a coveted Telly Award in the 1993 national competition.

Redlin's immense popularity can also be measured in the success of his book, "Opening Windows to the Wild, The Art of Terry Redlin." In its sixth printing, the book details his paintings, pencil sketches and biography. Always the perfectionist, he personally supervised the printing and production of this important project. A critical as well as a commercial success, the book was a Certificate of merit winner at the prestigious Printing Industries of America competition in 1988. His second book, "Terry Redlin, Master of Memories," was released in 1997 and was recently voted Best Art Book by those galleries polled for the U.S.ART survey.

terry redlinTerry Redlin derives the most satisfaction from his conservation work. Over the 17 year period from 1981 to 1997, his donations to Ducks Unlimited raised more than $28 million, setting an all-time record in art sales for wetland conservation projects. By his own estimate, he has donated several million dollars of art to other nonprofit conservation organizations.

Redlin's most compelling project is the construction of the museum to house his original art in Watertown, South Dakota, where he now resides. The Redlin Art Center, which includes a regional tourism office, and amphitheater, opened in the summer of 1997 and has seen more than 2 million visitors from all over the world. Terry Redlin donated the $10 million museum to the State of South Dakota in appreciation for an art scholarship he received after graduating from high school in Watertown.

He was honored in 1998 by the City of Sioux Falls, South Dakota by having an elementary school named in his honor. Terry Redlin Elementary School opened in the Fall of 1998.

Redlin's Story

Article reprinted from Saint Paul Pioneer Press Express, December 17, 1995

Written by Ellen Tomson, Staff Writer

Terry Redlin paints what the average person hangs over the couch. And his images hang over hundreds of thousands of couches.

Ducks struggling against the wind. Startled white-tailed deer. A cabin tucked into wooded lakeshore. A house on a hill with windows lit to welcome neighbors. Rusting wagon wheels. Someone lending a helping hand. Children fishing. Dogs, like loyal family members, following, guarding.

At dawn, at dusk, at night. As clouds thicken and darken or split open with light. Light—maybe more than his name—is his signature. Luminous sunsets. Shining water. Twinkling windows. Flaring yard lights. Cozy, glowing, warm, inviting.

They are images that have made him famous. Redlin has been the country’s top selling print artist according to national surveys of 900 leading art print dealers. At the peak of his career, his prints were sold in more than 4,000 galleries.

He gives a lot of money away—over $40 million over the years through his sales of his prints for Ducks Unlimited and other wildlife conservation groups.

And he has built the Redlin Art Center as a gift to his hometown and native state of South Dakota.

“He is out to please the public,” says his wife, Helene. “When you’re accepted by the public, it’s as if your personality and everything else you have done with yourself and your life has been accepted.”

“I want to please people,” he agrees. “And the average person, well, they think like I do. I think I’m an average person with a very average mind. So I just paint what I like.”

Eyes of Childhood

His teachers in elementary school called him “Windows Redlin” and seated him near the inside walls of their classrooms. Otherwise, he gazed at the sky and the landscape outside and thought about fishing and hunting. Or imagined new designs for model airplanes he would try to build. When he wasn’t daydreaming, he was drawing.

But neither he nor his parents ever talked of any particular job or goal he should aspire to.

He was born on a farm at the end of the Depression and lived in a house locals called “the dollhouse” because of its small size. For 30 square miles, nearly everyone living on the nearby farms were relatives.

He remembers watching sunsets while fishing with his mother on a creek bank. He recalls watching his father and a hired man hitch up horses to drive to town during a blizzard, and rooms lit by oil lamps when the electricity went out. Electricity was still special out in the country then. The single electric light in each room of the house was always turned off when you left the room.

When Redlin was about 5, his dad gave up farming and began repairing cars for a living. The family moved to town. In the neighborhood he grew up in, children roasted marshmallows over bonfires of leaves, played hopscotch, marbles and kick the can, built forts and flew kites. Ice cream was a treat and so was the 10-cent bus ride to go swimming at seven-mile-long Lake Kampeska. On weekends, families hunted or fished together.

Says JoAnn Roti, who grew up with Redlin, “When I look at his paintings now, I realize he’s captured our memories of childhood.”

At 15, Redlin was suddenly forced to consider what he would do with his adult life. He and a friend were hit by a drunk driver while they were riding a motorcycle. Redlin was on his way to his ushering job at a local theater and had begged the friend to allow him to ride for three blocks. His leg was crushed and had to be amputated.

“I decided I better get serious about something,” he says. “And art, I knew I could still do.”

He and Helene Langenfeld married when they were both 19, a year after they graduated from Watertown High School in 1955. They had attended the prom together. “He was friendly, a nice person,” she says.

Her family operated the Langenfeld Ice Cream Co., a name he includes on signs in some of his paintings.

South Dakota awarded him a “handicapped student” scholarship to the School of Associated Arts in St. Paul, Minnesota. He couldn’t understand why the state would do that. To his own way of thinking, “It was a gift. The chance that they’d ever see any return on that money was virtually nil.”

He hoped to become an illustrator, but he studied graphic design and layout in art school to help himself become marketable. His painting projects were overnighters, for class assignments. They often bored him, and he developed the habit of watching television as he painted. He and Helene lived in two rented rooms-a kitchen and a bedroom. She worked as a wholesale grocery company’s receptionist.

He landed his first job at Brown & Bigelow in St. Paul, sketching little drawings sized for the backs of playing cards. He discovered the company had a big morgue of calendar art in its main building-hundreds of paintings by illustrators such as Norman Rockwell. Redlin spent his lunch hours in the unlocked room. He’d line up a half-dozen Rockwells and just kind of study them as he ate his brown-bag lunch.

He quit Brown & Bigelow after two years. He missed hunting and fishing, and he was homesick. He and Helene returned to Watertown, where he landed a job as a draftsman for an architectural and engineering firm.

Six years later, he was a master of perspective. He could turn a building at any angle in a painting, place it anywhere. But by then, he couldn’t see a future for himself in Watertown. And he had three children.

He moved back to Minnesota when Webb Publishing in St. Paul hired him as a designer in January 1967. He figured he was set; this would be his career. He kept moving up. From designer to illustrator to layout artist to magazine art director. He learned to handle a camera. He worked as the quality-control director for color and learned printing. He didn’t draw any more.

Then, suddenly, the company laid off several artists, all older than he was. It would be just a matter of time, he thought, before it would be his turn.

“What do I like to do?” he asked himself.

On a Monday night, April 25, 1975, he told his family he was embarking on a five-year plan to become a wildlife artist. For the first two years of the plan, he would not pick up a brush. He would learn everything he could about wildlife and wildlife art. While still working at Webb-full-time-he would spend all his spare hours outside, observing and photographing.

“Everything he did was just so plotted and planned,” says his son, Charles Redlin, who was then a seventh-grader. “I don’t know if anyone realized how serious he was.”

Learning by Doing

The car pool guys he rode to work with slowed as they drove by, waving their coffee mugs out the window at him. “Hey Redlin, yah dummy…Whattya doing?” they yelled.

He was on his belly, crawling through a cornfield with a camera cupped in his hands. Though he really couldn’t afford to pay for gas on his own to get to work, he had abandoned the car pool. He wanted to be outside, as the sun came up, to capture images of dawn light and sky. He rose early every morning and worked for several hours, wearing overalls or Levies over his office clothes so he wouldn’t get them dirty. Then he drove alone to his art director job. He worked on his own projects again at lunchtime and at night when he got home.

When he was ready to paint, he created a studio in the basement of his Hastings house. He also set himself up to create his own prints from his paintings, to frame them and then pack and ship them. He designed and made his own mat cutter. He could cut a mat in seven seconds. He and Helene stained and varnished hundreds of picture frames out on their lawn. Neighbors joked about “Redlin Enterprises.”

He worked 120-hour weeks. Even his backup plans had backup plans. If he didn’t succeed with painting, he figured he could make it with a framing and shipping business. Or perhaps even a small gallery.

“I didn’t want to take any chance of …of not making it,” he says.

He sold his first two commercial prints, “Apple River Mallards” and “Over the Blowdown” in 1977 to Ben Stephens, who operated art stores in St. Paul and Arden Hills, Minnesota. Stephens gave him $10 for each.

“He was just a nice guy trying to make a buck, and they looked kind of nice,” Stephens says. “Everybody was trying to get into wildlife art—he was just another guy who walked in the door.”

On the way home in the car, Redlin and his wife exclaimed, “Isn’t that something? Can you believe it?”

They decided to enter half a dozen paintings with prints in The Wildlife Heritage art show—at Dayton’s in Minneapolis. “I was scared to death,” Redlin says. “But they just sold, and it was great. Then I really knew I was probably going to make a living at it all right…”

Redlin finally allowed himself to just paint, leaving the matting, the framing, the shipping and other aspects of the business to others. He began donating prints to Ducks Unlimited for its fundraising banquets.

“Morning Retreat,” his first major print for Ducks Unlimited, broke the $5,000 mark at three different banquets. At more than a dozen other banquets, it sold for more that $3,500. As interest in Redlin’s work and that of other wildlife artists grew, galleries started opening up in small towns all over the country where the banquets were held. And as the concept of limited edition prints gained acceptance, more publishers began representing artists and making prints available.

“Twenty years earlier, there wasn’t the infrastructure in terms of dealers or the acceptance of the product to really fuel Redlin’s popularity,” says Frank Sisser, editor and publisher of U.S. ART, a monthly publication with a circulation of 55,000 for buyers and collectors of limited-edition art work.

But Redlin, who had already worked 20 years as a commercial artist, did not quit his art director job at Webb until he was already making four times his Webb salary through his paintings. He was that cautious.

Getting Down to Work

Winter through spring: This is the time of year he returns to his studio to paint. The rest of the year, he signs his name. On each of about 150,000 prints. Boring.

He sets himself up with plenty of videotapes in front of a television. He writes with a soft-leaded pencil that has a fat, foam hair-curler wrapped around it. He needs a big grip to get through 1,000 prints a day. He stacks the prints like a deck of cards and lets them drop as his signs. Flick-flick-flick-flick…

So it’s great to get back to painting.

He sits high up on an old, wooden throne he made from an office chair. He mounted it on a wood disc with wheels so he can glide back and forth between his easel and tables arrayed with tubes of paint, some 400 brushes and other supplies.

His paintings often contain buildings and landmarks—churches, barns, houses, cabins, grain elevators—that are real, but the scenes he creates with them are all in his head.

Accuracy is important to him. He relies on photographs he has taken to render an old pickup truck or piece of farm equipment in exact detail. When he has a question about a farming technique, he turns to retired farmers for answers. Or, he goes out into a field, as he did for several hours in the middle of one night to produce “Night Harvest” which shows a farmer harvesting his fields by the glaring headlights of his combine.

He likes conceiving the ideas and designs for his canvases better than painting them. His facial expression when he paints, his son says, is that of someone having a headache.

When he started out, strictly as a wildlife painter, a typical image was a straight, open slough with ducks, grass and sky. For the first 10 years, he did not dare to include people in his landscapes. His first experiment with people was subtle, one figure in a sleigh. But the print, “Coming Home”, was an enormous success.

Since then, he has moved more and more toward nostalgic, storytelling themes, rooted in Americana. He describes his style as “romantic realism.” One example is a series of eight paintings that illustrate “America the Beautiful”.

When they were last on the market, Redlin paintings sold for $50,000 to $75,000. Now, they could be considered priceless because they are not for sale. He has not sold any originals since 1985, when he agreed to his son’s suggestions that he build the museum to house them.

“The idea of the museum is to bring in outside tourism money for the state, to pay back what South Dakota gave me for tuition to go to art school,” Terry Redlin says. “They grubstaked me, so I’m just paying them back now.”

Golden Years

After a lifetime of artistic achievements, Terry Redlin announced his retirement on June 27, 2007, from painting and print signing. Redlin, who is widely known as “America’s Favorite Artist,” has accomplished what he set out to do. “I wanted to tell stories with my paintings, to remember the experiences of my youth, and to imagine and capture forever events that have been related to me by older folks I have had the pleasure of knowing,” said Redlin. “America’s rural past, in my eyes, was a wonderful place full of both beauty and opportunity. How fortunate I’ve been to spend my life creating memories of those distant times for others to enjoy.”

It is rare that an artist’s work is so original in style and so immediately recognizable that it actually evolves into a genre of its own. Such is the case with Terry Redlin, whose serene, heartwarming scenes have been gracing art lover’s walls for three decades. Beginning with the 1977 release of “Winter Snows,” Terry Redlin enthusiasts have collected over 2 million art prints and an even greater number of collectibles and home décor products — all inspired by his unique artistic talent.

Terry would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to the countless dealers and collectors who have supported him throughout his career. He takes great satisfaction in knowing that his work will continue to inspire others and that the future release of new Terry Redlin products will support his two most cherished causes—the Redlin Art Center in Watertown, SD, and the preservation and restoration of rural America.

Please note that many Terry Redlin signed print editions remain available at their original issue prices at this time—but in limited quantities. No additional prints will be signed and there will be no new paintings.

Terry is looking forward to enjoying his retirement in the home he built on a spot he fished from as a young boy. It took him a lifetime of work to get back to the shores of Lake Kampeska in Watertown. Redlin noted, “An American novelist once told us that you ‘can’t go home again.’ He was wrong. In my mind, I never left home, even when physically away. And when I finally returned, it was a great relief. I had a deep feeling that, finally, things were going to be okay. I was reconnected to my past, and to a childhood that was magic.” Redlin plans to enjoy his retirement in Watertown surrounded by the family, friends and places that have inspired him for nearly 70 years.

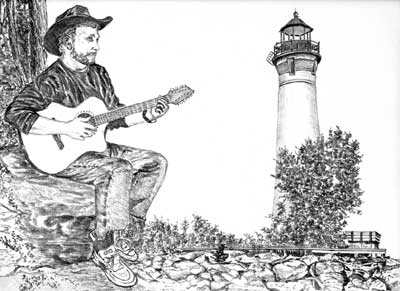

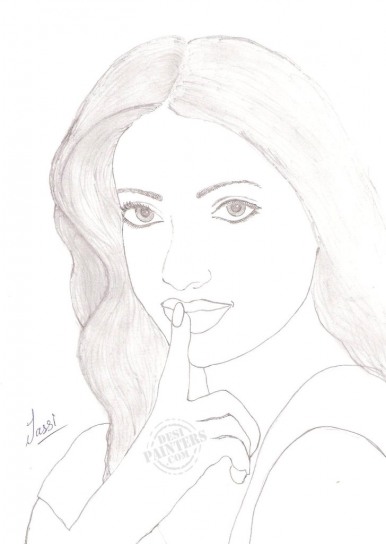

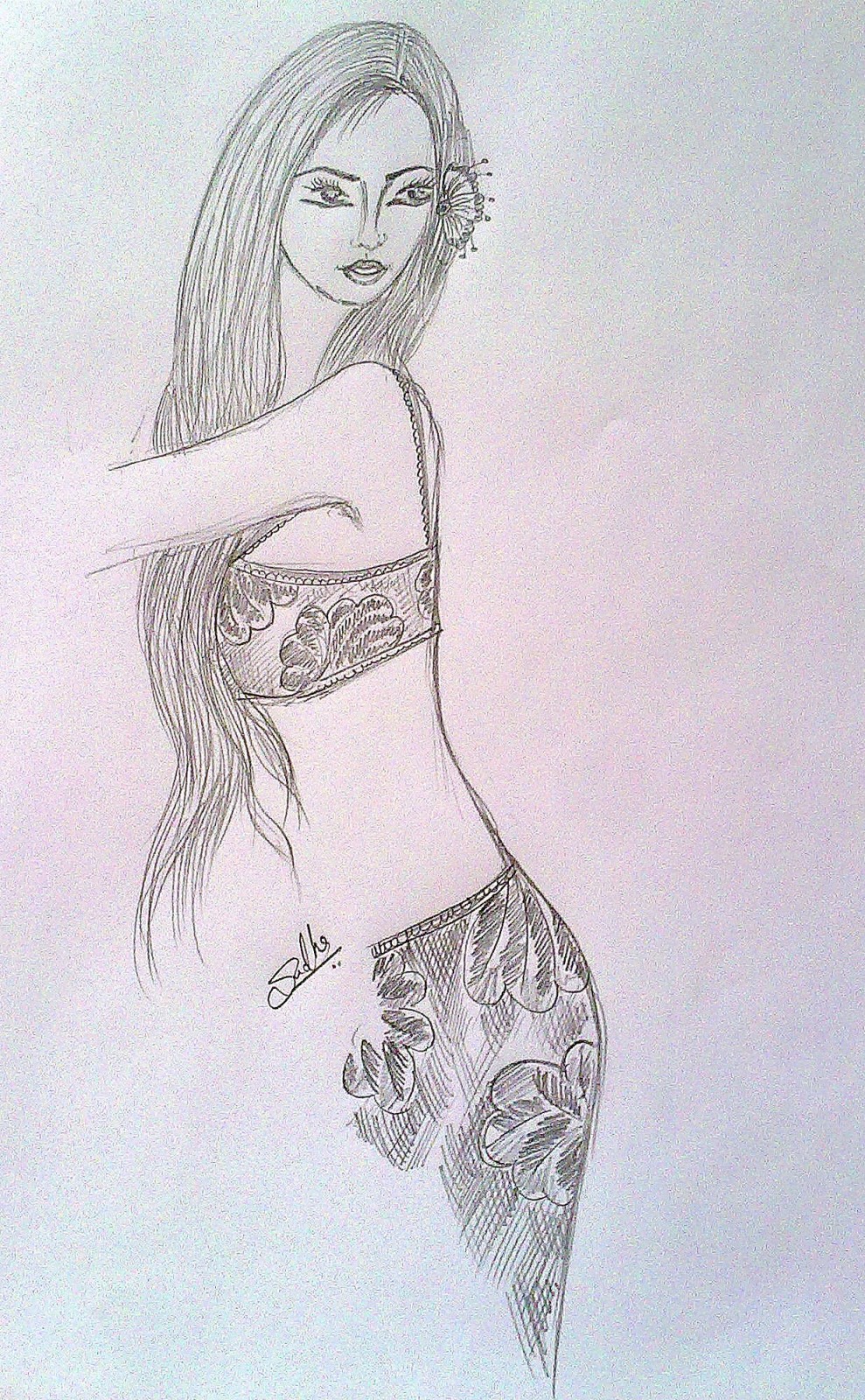

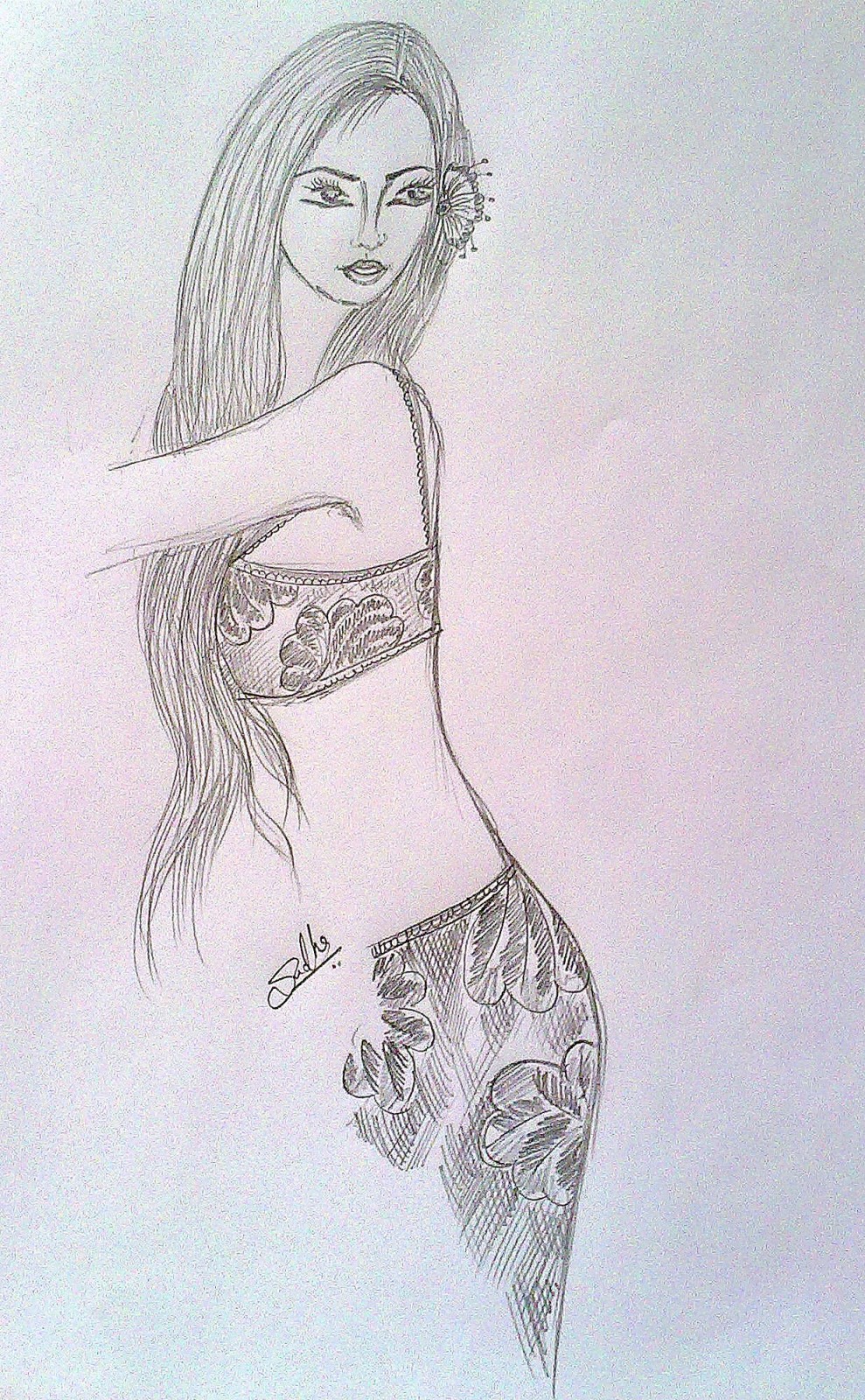

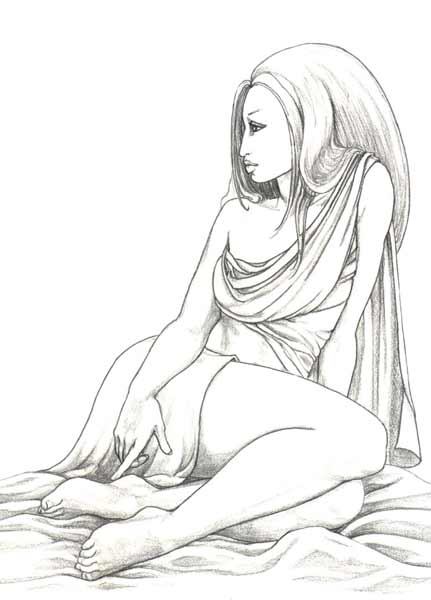

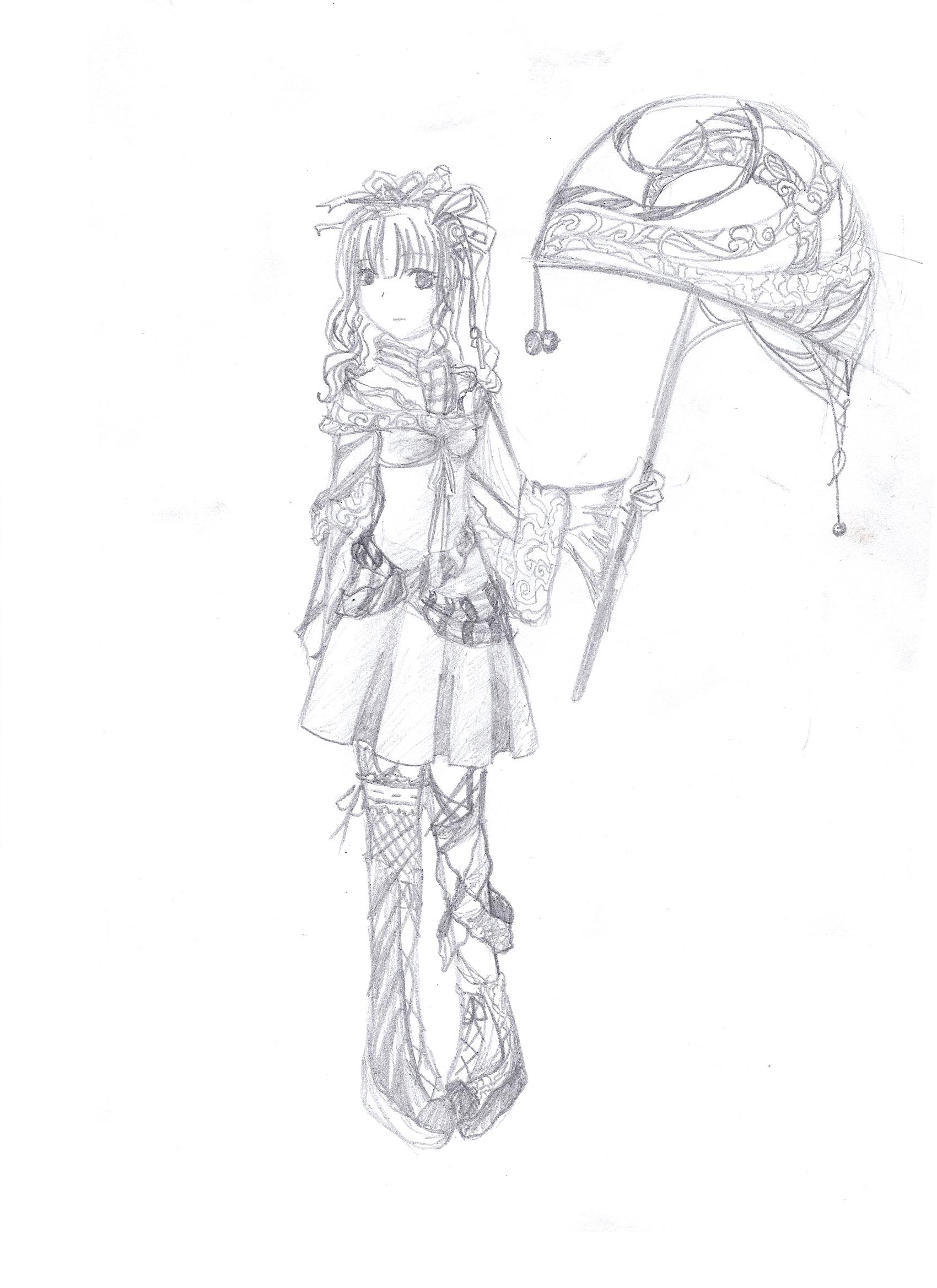

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

Beautiful Pencil Sketches Of Nature Of Sceneries Landscapes Of Flowers Of Girls Of People Tumblr Of Roses Of Eyes Of Love

No comments:

Post a Comment